Fukuoka Art Museum - Fukuoka, Japan

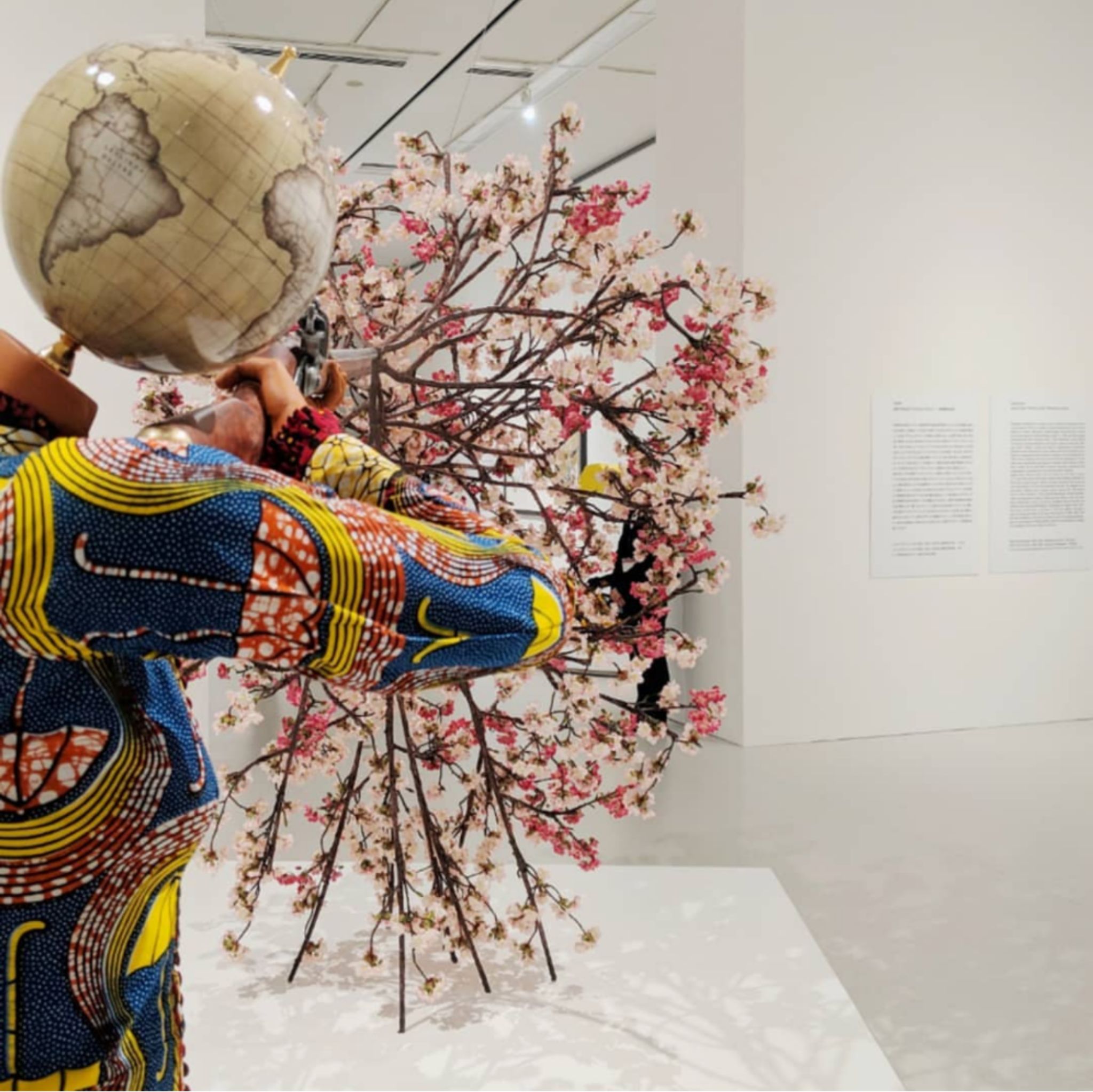

YInka Shonibare CBE, '“Woman Shooting Cherry Blossom”, 2019.

What do we mean when we use the term “global”? What’s inclusive in ‘global’ and what is subconsciously discarded?

This word whose definition denotes all-encompassing is sometimes limiting. For instance, I describe my endeavors in travel and art as “Traveling the world to indulge in art.” Yet my travel purview consisted of the Americas, Europe and African continents – not quite inclusive of the world and pure globalism. Absent from this list was the world’s largest and most populous continent, Asia, that was, until the first solo exhibition by Yinka Shonibare CBE in Japan, at Fukuoka Art Museum, beckoned me.

The exhibition, titled Flower Power, was on view until May 26. The museum, emerging from a two-years’ long renovation, opened with Shonibare’s solo show and another exhibition of select works from its collection.

Flower Power explored the relationship between the museum's collection of pe-modern Japanese and Asian textiles and Shonibare's signature Dutch wax batik fabrics. Shonibare employs this fabric in sculpture, installation, video and even in works on paper to explore colonialism and cultural identity in the contemporary context of globalization.

The exhibition included works from throughout his career and concluded with the central piece, Woman Shooting Cherry Blossom (2019) - a new commission. At the entry to the show a brief history of batik fabric was outlined: A Dutch appropriation based on Indonesian design, its later introduction to the African colonies in the 19th century (because the style was rejected in Indonesia), and its subsequent popularity and association as an “African” textile.

There was a singular walking path through the exhibition space and while it was fine to saunter through the space with frequent pauses to take in the layered meanings of Shonibare’s art, back tracking seemed to be discouraged: I saw another viewer attempt to walk backwards to revisit an artwork and was, very politely, ushered to keep moving forward.

Cherry Blossom was just as dynamic for the bouquet of blossoms, called ‘sakura’ in Japan, as for the dress of the mannequin, an Edwardian style popularized in Japan during the Meji period (1868-1912) – a period of Western modernity and industrialization in Japan. The globe-headed figure fires a rifle confidently but rather than gunpowder blossoms emerge. The bouquet is large and nearly matches the height of the figurine. Shonibare uses the cherry blossoms as a symbol of hybridization. The female identity is rooted in Japanese tradition but the figure touches on global feminism: inscribed on the globe are the names of women activists from around the world. The gun in the possession of a woman figure, with fingers gripped on the trigger, alludes to female empowerment as well. The cherry blossom was personally meaningful to me. I grew up in Washington, DC, a city lively with cherry blossoms that were a gift from Japan. The blossoms form a national cultural identity for Japan and a local identity for DC. This cross-cultural exposure from youth made traveling to Japan for this exhibition come full circle. Woman Shooting Cherry Blossom was beautiful and powerful.

Outside of this exhibition the museum also put on display 250 artworks from its collection, including works by Andy Warhol, Anish Kapoor, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama and Salvador Dali, among others. There was, if you will, a global offering of major contemporary artists.

After Fukuoka I flew to Tokyo. I traveled to Japan with the determination to indulge in an unbridled curiosity of this country I’ve never been. Although this was my usual mindset when traveling, a 26-hour journey from the US to Tokyo and Fukuoka made me even more resolute. This even extended to my hotel experience – staying in a Japanese pod. The American convenience store 7-11 is extremely popular in the cities I visited in Japan, albeit their presentation was more polished. Sushi and ramen were daily meal staples that I never lost an appetite for. Shonibare, at the opening of his first exhibition in Hong Kong even said, “We eat sushi then we go to school and speak English.” This global interconnectedness reflects in Shonibare’s work.

Photograph by Nadia Sesay.

Photographs by Stephen White / James Cohan Gallery.